(From GASSED: The True Story of a Toxic Train Derailment, Book 1 – The Spill. Chapter 1.)

“While the oxygen lasts, there are still new things to love, especially if compassion is a form of love.” – Norman McLean1

The silver ribbon awaited. On the cold, drizzly evening of April 10, 1996, engineer John Caswell clocked on at the Yardley rail yard outside Spokane, Washington. Employed by Montana Rail Link, Caswell prepared to take over a Burlington Northern Santa Fe train headed east to Missoula. MRL often bridged trains for ‘BN’ through Montana. While they waited in the yard office, assistant engineer Billy Schutter studied the consist, looking for ‘bullets’ of dangerous cargo.2

Cars 11th through 14th grabbed his attention—four tankers of liquid chlorine. Immediately after came a tank of corrosive liquid waste.8

A string of “Dangerous.”

Further back, butane gas and a load of hydrochloric acid.

Chemistry on wheels, but not so unusual. Stretching his legs in the yard, Schutter eyeballed the train. The chlorine lay a good 500 feet back, far enough to slide to the back of his mind.

They had five engines to pull 71 cars, 5551 tons, up the mountains. A modern-day wagon train of food, materials, and toxic chemicals.2

They also carried human cargo. John Elmer Smith, Jr. and “Lucky” had hopped an empty gondola two cars past the string of tanks.12 Smith was a genuine free spirit, a 70-year-old riding for adventure.13

In the open car, the men likely huddled beneath a tarp to keep dry of the cold rain.

When they took command, Schutter ran the locomotive under the supervision of Caswell. Schutter, 30, was five weeks from being certified a licensed engineer with a big jump in pay.3,8

Caswell’s grizzled beard conveyed a veteran of the rails. Forty years old, for the past three months he’d been lead engineer on the trip between Spokane and Missoula, where he lived.7 Two hundred eighty miles lay ahead, a route the men had ridden hundreds of times.3,8

They drove north to the Pend Oreille River where it crossed the Idaho border, then east across the narrow neck of Idaho until Sandpoint on the northwest corner of Lake Pend Oreille. Here the MRL line officially began, forty miles from Montana. Mountain railroading awaited—canyons and cascades, trestles and truss bridges, tunnel after tunnel, curve upon curve.

Under the right light, riding good rail felt like surfing on silver.

At Hope, they began running upstream beside the Clark Fork River, which would accompany them all the way to Missoula. Near the pass into Montana, they hit a rough spot at a crossing and felt a drop that “literally made the engines jog off the rail,” Caswell recalled.7 Schutter bounced off the control stand.

Je-sus!

They called it in to the dispatch center in Missoula, and as they drove on, heard on the radio that the section man would watch the next train passing west, now slowed to 10 mph because of the bad spot.7,8

The rough track jarred Schutter’s memory. Just a week ago, he talked to Mr. Brodsky—William Brodsky, president of MRL—about the shape of the track. Schutter’s train had stopped in Frenchtown west of Missoula, and as he checked an open boxcar door, Brodsky happened to be parked nearby and helped Schutter close the door. When Brodsky gave him a lift back to the head end Schutter shared his concerns about rail. He thought they were headed for a bad derailment someday—it was rough on the western end. Brodsky told Schutter he knew about the bad conditions, but with so much freight traffic, they couldn’t repair a lot of it right away.8

The heavy climbing done, at Noxon, the first Montana station, they dropped to three locomotives. Just beyond, they encountered another rough spot, one they reported two days earlier. In fact, they had heard it reported by other trains for about a week and a half, so they didn’t bother again tonight. It hadn’t been slow ordered either.7,8

Riding good rail was almost as smooth as glass.

Caswell drove trains under BN before MRL leased the line in 1988. On the BN, they usually fixed rough track within an hour, or issued a slow order meantime.14

Now, business was booming with grain freight, and MRL ran some 20 trains a day west out of Missoula. As Schutter understood it, time was money and some of this groaning rail would have to wait.

They rolled east, carving curves in the drizzly dark. Wild, lonesome Montana.

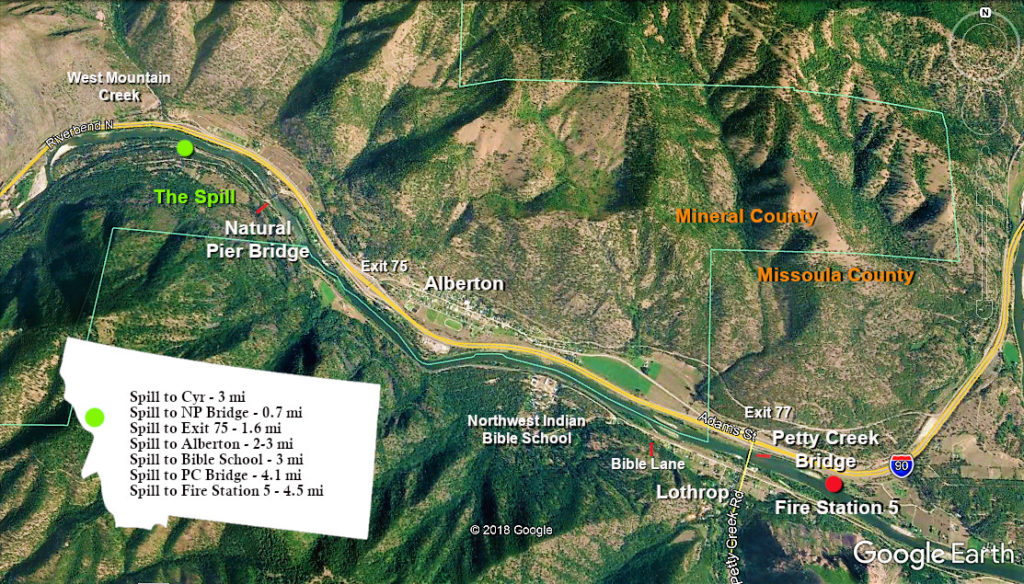

Soon, Caswell took over as lead engineer and drove on to Paradise, the juncture with MRL’s local north route and the main south route to Missoula.7,8 The southern River Line hugged the Clark Fork River as it doglegged into Mineral County, where track, river and the interstate, along with the odd ranch, crowded the mountain corridor. The old Milwaukee Railroad had once squeezed through as well, though nothing remained but a trail of ghosts and gravel.

They passed Superior, the county seat, population 881. Most of western Montana comprised folds of mountains, with civilized folk sifted in the valleys. Others hid in nearby cracks.

These were strange times in Montana. Just last week, Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, was arrested outside Lincoln in his sparse cabin, 80 miles northeast of Missoula. Even now, several outlaws were holed up at a ranch in a standoff with the FBI. The “Freemen” outside Jordan in their self-proclaimed “Justus Township” were wanted on warrants ranging from writing millions of dollars’ worth of bogus checks and money orders to threatening to murder a federal judge.

But these trainmen felt no menace tonight. They were comin’ home.

As they drove past the Alberton Gorge, a pinch and plunge between shouldering mountains renown to rafters, Schutter felt home. He’d worked and hunted and breathed these mountains all his life. Just a few miles further lay his town on the bench above the Clark Fork.

Alberton’s three hundred and fifty odd souls were dead asleep now at 4:00 am. Schutter would have to drive back thirty miles from MRL’s yard in Missoula to join them. They’d been on duty ten hours.

It was 39 degrees and calm, and a light drizzle persisted. Heavy-bellied clouds swaddled the mountains.

The track tipped slightly down slope as they entered the last curve before Alberton. Around milepost 155, Caswell throttled down and set the cars’ air brakes. They had crept up to 42 mph. Less than two miles ahead, beyond the curve, the speed limit would drop from 40 to 35 mph, and they had nearly nine tenths of a mile’s worth of train to respond.3-5

As they entered the right-hand curve, they saw in the headlights ribbon rail glistening alongside the track. Schutter noted tie plates sitting on the wooden tie ends by the new rail. He hadn’t noticed the rail before and figured crews were fixing to replace worn track. The mild curve would straighten after 1000 feet before ducking under the Natural Pier Bridge ahead.5,7,8

Schutter, riding the high side of the curve, closest to the river, had a funny feeling wash over him. Coasting, they had just begun to slow below 40 mph when the locomotive dipped to the left as if the track had gone soft, and then it sounded as if they ran over something loose and crunchy, like metal or rocks, even through the muffle of their earplugs. Their engine shuddered.

Jesus.

Caswell wondered if a section of rail was flat gone. Schutter thought the train had derailed—the jolt was much rougher than at Clark Fork, the shudder of a giant bull, nearly bucking them off. And then the engine righted itself and smoothed out straight again.

They looked at each other and blurted in unison, “That didn’t feel good.”8

“What the hell was that?” Caswell asked.7

Two days ago, they’d come through and felt nothing.

In fleeting seconds, they had dropped to 33 mph, and then the air brakes ‘dynamited’ into emergency. Now they knew the train had derailed—entered the ‘Big Hole.’ Caswell quickly put the automatic brake valve into emergency and bled the air off the locomotives so the brakes wouldn’t stick. Looking back, they saw sparks flying, lighting up the scene. Schutter saw 100-ton freight cars piling up like goddam toys. Gripping the console, he hung on, helpless, waiting for the forces of physics to find rest for their engine and bodies. As they slid by, a telephone pole made an abrupt about face, the cross arm spinning in salute. Electric wires flew through the air, snapping. He marveled at the power and spectacle.8

His first derailment! Schutter thought it “pretty neat.”

After they had gone into emergency braking, they traveled maybe 600 feet before coming to a dead stop. Since hitting the rough spot, less than 20 seconds had passed.

“We’re on the ground,” Caswell said grimly, wondering if that included any locomotives. They popped their earplugs. Their lead engine was just past Reardon Crossing.5

4:07 am.

John Elmer Smith, Jr. and Lucky tossed about the empty car like loose change as the gondola snapped free and spat out into a ditch, jarring to rest tilted against the far bank. Bruised and rattled, but they hadn’t gone in the river, thank God. They hadn’t died.

The wreck deafened, a devil’s symphony of metallic crunching, screeching, and deep thuds that muffled the men’s groans. And something else—an immense howl.

Two smells overwhelmed them: the acrid bite of chlorine and some other ungodly stench. Smith and Lucky had little inkling of their surroundings, but shared one imperative—run!

At three-thirty that morning, signal maintainer Bob “B.J.” McComb woke to a phone call that a track light was out at Rivulet, ten miles west of Alberton. McComb lived at the end of Plateau Road, a dead end above the river, and drove east over two miles to the Natural Pier Bridge to reach I-90 before heading west.

He passed the eastbound train minutes before it derailed.10

Schutter grabbed the train consist, remembering the cargo tethered behind them. Four tanks of chlorine maybe an eighth of a mile back. They hadn’t traveled much further than that since the bad spot. Those tanks could have derailed right there.

“Yeah, Carter, we’re on the ground here,” Caswell radioed to MRL dispatch at 4:12 am.9 Missoula West dispatcher Carter Meyer was his brother-in-law.

“We felt a big thump on the engines,” and a couple seconds later the air went. Caswell told Carter about wires throwing sparks.

“Be careful there. Let me know what you find, please,” Carter said.

The engineers didn’t smell anything, and that was good news, as MRL wasn’t required to carry gas masks in the cab.15 But they had to check for damage and Schutter knew it was risky.8

Schutter put on his gloves, grabbed radio and lantern and left by the front door to enter the drizzle. The fireworks had ended and the spine of the train lay broken in the dark. He climbed down the steps until he was below the cab window of Caswell.

B.J. McComb overheard communications and radioed the crew, asking exactly where they were. A fellow local, Schutter could be precise with McComb.

“We’re at Reardon Crossing.”9 Over half a mile west of the Natural Pier Bridge.

Schutter took four or five steps toward the rear and met something powerful.

“It smells like we’ve got some chlorine going here, too,” he told McComb. “Going to need some hazmat!”

Schutter ran back inside the cab and closed the door, and now Caswell smelled it too. A dry thing.

“I’ll head back up that way,” McComb said. “Maybe I can give you a hand.”

Schutter coughed as his throat closed tighter.

“The chlorine is taking the air away from us!”9 His eyes burned and he doubled over choking.10

“Goddam it, pull the fucking pin and get out of there!” McComb said he would notify the sheriff’s office in Superior. “Don’t stand around inhaling that shit!”

“Bob, can you get up here quick?” Caswell pleaded.9

McComb couldn’t be quick—he was seven miles to the west, and with the highway median a quagmire, he would have to continue nearly to Rivulet before he could exit and come back.

“I’ll be there in a minute.”

Caswell had been on six or seven derails before, but nothing like this. He verified a chlorine release with Meyer, who overheard the chatter with McComb.

“We’re right at the approach to Lothrop,”9 Caswell told Meyer, coughing. The Lothrop siding began at Petty Creek, over four miles east, and then ran back west a couple miles. Caswell, not a local, had referenced the nearest track siding. Carter would translate their general location as “just west of Lothrop” and said he’d send an ambulance to Lothrop—four miles away.

“It’s choking us,” Caswell pleaded.

Another train crew listening in while sitting at Frenchtown, fifteen miles east, told Caswell they would run their engines out and grab the men. But Meyer told them McComb was on the way and didn’t know if more help was needed.

“You’re too far away,” Caswell told the Frenchtown crew.

Meyer didn’t understand the gravity of the engineers’ predicament. He soon told another employee that the derailment had spilled some chlorine but he didn’t “know how bad or anything like that.” Meyer assumed that the crew would somehow meet up with the ambulance at Lothrop.

Now the engineers could see in the train’s headlights a yellowish-white fog creeping along their engine about three feet high. The tide-like gas embraced them as it passed.

“It’s all over the ground here,” Caswell told McComb. He didn’t think McComb would be able to get in to help them. Meanwhile, Schutter read from the manifest’s hazardous materials instruction sheets.

“It says ‘apply water to knock down vapors.’”

McComb said he’d contact the Alberton volunteer fire department. “You guys get clear of it?” he asked.

Caswell had tried to pull free, but they weren’t moving.

“We’re not clear of it. We’re still in the power here.”

Just then a car approached above on the frontage road, and then stopped, its headlights facing the train. Caswell blinked the train lights and blew the horn as a warning to get away. As gas continued to spread past the engine, the car lights receded. The smell in the cab worsened, the windows fogging on the outside, adding to the feeling of being trapped in a gas chamber. As Caswell struggled to breathe, Schutter grabbed paper towels to put to their faces to filter the gas.

They still couldn’t budge the engines. Each one weighed 360,000 pounds.

Now Caswell contacted the Frenchtown crew and asked if they could come, and Frenchtown radioed back to dispatch to get permission. Meyer finally asked Caswell for the exact location of their train.

McComb broke in to offer instructions. He had arrived at the Natural Pier Bridge.

“Natural Pier Bridge, and then turn right. Take the first turn off to the right, and they are right there. Natural Pier Bridge is on the frontage road just west of Alberton.” Carter repeated this, but more accurately speaking, the road south of the river and west of the bridge was Plateau Road, and the first right off of it was Reardon Lane, which led down to Reardon Crossing and the river. The crossing was over half a mile west of the bridge. Regardless, Meyer roughly had a location—west of the Natural Pier Bridge at Reardon Crossing. No one thought to give or ask for a mile marker.

McComb told Meyer he had started across the bridge “but that cloud’s coming across it,” so he was backing off.9 McComb saw the gas advance up the river, a yellow mist that spilled across the bridge deck. Even in his truck cab, it smelled horrific.

“There’s quite a few people here. Wake them up. Get ‘em moving, I guess,” he told Meyer, the first call for evacuations. Along with Plateau Road, the frontage roads on either side of the interstate leading to Alberton were dotted with homes.

McComb advised the engineers to get out now.

Meanwhile, Meyer told the Frenchtown train crew to hold off on a rescue.

“We’ve got emergency personnel responding,” he said. Meyer had notified 911 and MRL brass. “We’re not exactly sure what we have,” he warned Frenchtown.

The Frenchtown crew radioed back Caswell.

“They’re not going to let us out.”

“We’re moving,” Caswell said, determined to find a way.

Caswell had already considered trying to unhook the stubborn engines, but neither he nor Schutter wanted to face the gas.

“We’re not going to make it out of here if we don’t try something,” Caswell argued.7 Schutter saw his own fear reflected in Caswell’s face. Schutter then left the cab for the second time to try and see how they were hooked up, but once on the ground he was immediately forced back in, hacking and choking, nearly overcome. Schutter could breathe out, but drew little air back. His vision blurred.

Caswell implored Meyer they needed help now.

About fifteen minutes had passed since they were down, and the reek of chlorine filled the cab. They sat gasping and choking, knowing they had to leave but not knowing how.

Schutter’s wife and two children lived in Alberton, two miles east. Of immediate concern was his mother, Darlene Gonzales, who lived just across the river and the interstate directly across from his position, maybe a quarter or half mile away. He grabbed his cellular phone and called her.

“Get out—we’ve got a chlorine spill!”8 Gonzales told him she could already smell it at the house. Schutter said he loved her and would see her at the hospital, though he wondered if he would ever see his mother again.

They were dying, and no one was coming.

Nauseous, Schutter remembered from his Navy training that it might help filter chemicals better if he wet their paper towels, so he began soaking a bunch. But to Caswell it felt like trying to breathe through a tabletop.

Now Caswell rose and stepped to the door, determined to uncouple the engines.

“Wait!” Schutter cried.

Opening the cab door, Caswell seemed to walk into a brick wall, or a door to nothingness and the vacuum of space.

“Shut that door! Don’t go out there!” Schutter cried.

Smith and Lucky crawled with tender bodies out of the gondola and paused on the threshold of a poisonous mist, vague immense shapes looming above the ditch. A moonless night, even in broad daylight a clear path to escape would have taken some cool thought. Now, instinct and panic drove them to find air to breathe.

Lucky worked his way around the corner of the car and clamored up the ditch bank into the forested slope and kept climbing.12 Smith, perhaps disoriented and beginning to suffocate, made his way up to the rail bed and squeezed through the wreckage toward the flat bench between the track and the river, pushing through brush, where he fell.

Caswell had reset the engines and made several attempts to move, but the engines only strained, and the men suspected they were hooked to a derailed car. There was no way of knowing from the cab how far back the first car was off rail, or if the engines were off too.

Their whole world was the cab, a small hut at the head of the locomotive.

Caswell’s thoughts raced as he paced the cab hacking and choking, searching for a plan. Like a locomotive banking too fast, his mind teetered between control and imbalance. He had to focus.

Get out of here!

“I think all we can do is try to uncouple the cars,” he implored Schutter. “Nobody’s coming. We’ve gotta get out ourselves. If we don’t, we’ll die.”7

They couldn’t make a run on foot. The icy waters of the Clark Fork lay to the north, the mountainside to the south. And the chlorine seemed to spread everywhere. Their only hope was the train, but if they waited much longer, it would be their tomb.

They were both fairly certain they would die.

Caswell told Schutter it would be better if he went. Schutter, tall and athletic, was younger, and Caswell, an ex-smoker with a history of asthma and bronchitis, wasn’t in nearly as good shape. The plan was simple—run like hell, pull the pin and signal Caswell. Schutter would have to run past the three engines, about 195 feet. A piece of cake—without chlorine gas.

Caswell began backing the engines into the cars to bunch them up and ease any tension. Grabbing wet paper towels, his lantern and radio, Schutter stood by the rear door, directly behind the engineer. Before he left the cab for the third and last time he turned to Caswell.

“Keep trying to move, and if you break free keep going, because I probably won’t be able to use the radio,” Schutter instructed. Just go.

He would try to jump aboard the last locomotive.

“I’m not coming back, John. But one of us is going to get out of here.”8

As Caswell finished backing the engines, the cab door slammed shut and Schutter was gone—bravery compelled by desperation. Caswell spun to look back and saw the glowing lantern disappear as Schutter moved in.

Pull the pin, Billy!

Schutter wouldn’t remember his run. After slamming the cab door, he remembered pulling the pin to uncouple the third engine from the rest of the train and then signaling Caswell with the lantern.

Caswell immediately attempted to move. Nothing. Again. Nothing. After several attempts, he finally felt the locomotives break free—Go go go!—and he prayed that the engines were all on rail and that the gas wouldn’t strangle them, for without oxygen, the engines too would die. But the locomotives chugged, freed after twenty-five frantic minutes on the ground. Caswell pushed the engines east, harder, in quest of air, knowing he had four miles to the Petty Creek crossing and the care of human beings.

Caswell drove them to oxygen, and Schutter had set them free.

They were oblivious of the two men who had fled from the boxcar, where one climbed and the other fell and died.

As McComb drove along South Frontage Road he heard Schutter gagging on the radio, saying they’d pulled the pin and were moving. McComb wanted to intercept the train at Petty Creek, but as he headed east, he quickly stopped to warn some residents of the coming gas. He also called his son Kurt on Plateau Road, to tell him to evacuate their family and neighbors.

The gas was moving east, McComb told Meyer, “getting worse here all the time.”9

About a mile and a half down the line, just opposite the western outskirts of Alberton across the river, the engines cleared the cloud of chlorine. Caswell could breathe more easily—or at least he had good air to try and fill his lungs. Then he began throwing up and coughing violently.

After signaling Caswell, Schutter found himself flat on his back on the rear of the walkway platform of the third locomotive, raggedly sucking fresh air. He didn’t remember getting there, or when he had passed out. A train was bearing him through the black night. He heard a whistle, a train whistle, his train, and then Caswell’s voice on his radio.

“Are you there? Billy?”

“Yeah, I’m on this last unit,” Schutter gasped. “My lungs are burning real bad. I think we’re out of it.”

“I’m trying to suck in as much air as I can,” Caswell said.

Sweet, cool, Montana air.

It was about 4:40 am.

Caswell radioed Meyer that they felt much better and were headed for Petty Creek.9

“That’s a bad hit,” Meyer told his brother-in-law.

“You ain’t a jokin’,” Caswell croaked.

He cranked the engines east.

Schutter’s heart pounded through his chest. His eyes burned, his skin felt odd and he still couldn’t draw a full breath. Yet, the exhilarating realization hit him that they were both alive and might get out of this thing after all. Struggling to his feet, he walked unsteadily toward the lead engine by maneuvering along the platforms and through the cabs, and rejoined Caswell.

Though they had escaped with their lives, the men had little inkling that the derailment would forever change them. Even in sleep. Billy Schutter would dream an enduring nightmare of seeing the departing locomotives leave him behind.8

Jesus.

Within five minutes, dispatcher Carter Meyer received a call that a train had jumped the track at a rough spot near Noxon. Four engines and 16 cars were on the ground with diesel leaking and a report of sparks and flames.9

“It felt like it kind of bottomed out on a real low spot,” the engineer told Meyer. Cars tumbled down a bank and piled up.

Initially, in this charged time, authorities considered the possibility of coordinated terrorist attacks—sabotage.6,11

But the coincidence was actually rooted in poor track conditions—an attack from within. In hindsight, Caswell and Schutter’s train went one-for-two in avoiding catastrophic derailment this night. But this second MRL derailment in half an hour was not particularly important right now.

Ninety miles to the east, a gas cloud expanded, drifting toward the sleeping town of Alberton.

References

1-Norman Maclean, Young Men and Fire (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992, Forward).

2-MRL train consist for train 01-196-10, April 10, 1996. (Alberton Incident public document files, Missoula County)

3-MRL train 01-196-10 timetable, 1996. (NTSB/FRA Alberton files)

4-FRA accident investigation report, 1996. (EPA/FRA/NTSB Alberton files)

5-FRA engineer interviews, April 11, 1996. (EPA/FRA/NTSB Alberton files)

6-Jim Greene, MT Disaster Emergency Services, Alberton Train Derailment Staff Ride, May 2, 2015. Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. (RL Scholl video recording)

7-John Caswell deposition, January 27, 1998, in Mayo et al v. MRL (CV-98-109-M-DWM) (US District Court, District of Montana, Missoula Division).

8-William Schutter deposition, January 27, 1998, in Mayo et al v. MRL (CV-98-109-M-DWM) (US District Court, District of Montana, Missoula Division).

9-MRL West Dispatchers tapes, April 11, 1996. (NTSB Alberton file)

10-B.J. McComb, RL Scholl interview, 2001.

11-Tom Ellerhoff notes, Montana DEQ files, April 12, 1996.

12-Technical Group meeting notes, April 17, 1996. (Alberton Incident public document files, Missoula County)

13-Tom Zeigler interviews, RL Scholl, 2009, 2010.

14-Austin trial notes, 2001, for Austin v. MRL (CV-99-39) (US District Court, District of Montana, Missoula Division).

15-Kenneth Holgard, FRA, interview, RL Scholl, April 4, 2000.